By Jared L. Olar

Local History Program Coordinator

As Pekin’s Bicentennial Year continues and we now find ourselves in Black History Month, it is fitting that we turn our attention now to Pekin’s African-American history. Compared to most other areas of our city’s history, this is an aspect of Pekin’s history that has been little researched and whose stories have been little told (which is why I have made it a point over the past five years or so to devote time to researching and writing about Pekin’s Black History here at “From the History Room”).

In fact, up till now the most extensive account of Pekin’s African-American history in the standard published works on Pekin’s history is that found in the 1974 Pekin Sesquicentennial volume. While the Sesquicentennial’s account is far from uninformative, the very nature of a celebratory commemorative historical volume dictates that its treatment of its topics will be more in the nature of a review or survey – and one that will tend to downplay or overlook aspects of history that are unpleasant, lamentable, scandalous, or matters of controversy or contention. Yet I also find it a regrettable omission that the Sesquicentennial’s author did not tell the story of Pekin’s Christian ministers, Rev. Lewis Andrew of First United Presbyterian Church and Rev. Larry Conrad of First Methodist Church, who with their Marquette Heights colleague Rev. David B. Jones answered the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s call to clergy to come to Alabama in March 1965 in the struggle for civil rights for America’s blacks, as was reported in the Pekin Daily Times back then. However, the Sesquicentennial author did make sure to tell (on page 180) of Sen. Everett M. Dirksen’s crucial role in getting the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed.

In this article, I do not hesitate to discuss some of these difficult or unpleasant matters, for I am of the opinion that Pekin’s story should be honestly told, including the brighter and delightful aspects as well as the darker and unpleasant episodes – if for no other reason than to illustrate just how very far Pekin has come from its darker days and how many positive changes have taken place since then.

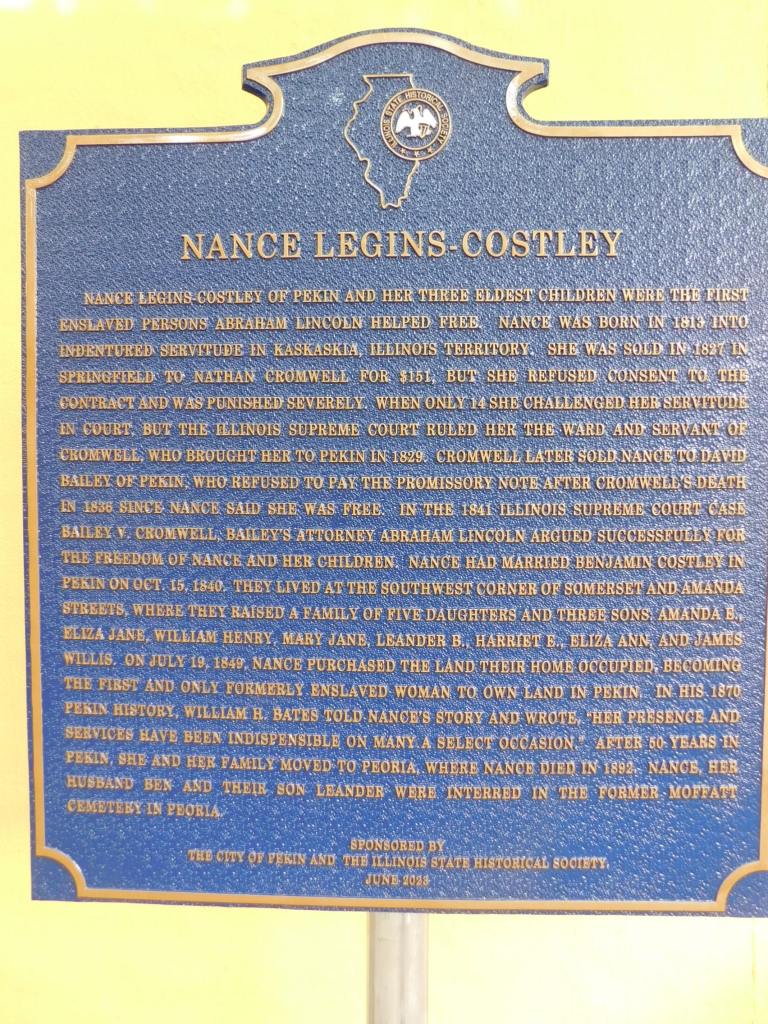

Nance Legins-Costley

One of the strengths of the Sesquicentennial’s treatment of Pekin’s African-American history is its account of Nance Legins-Costley (1813-1892), whose story has been spotlighted many times in recent years and who, along with her son Pvt. William Henry Costley of the 29th U.S. Colored Infantry, is now rightly honored with historical markers and a downtown Pekin park named and dedicated in her honor. Nance Legins-Costley is one of Pekin’s most notable and historically significant pioneer settlers, and she was also Pekin’s first known black resident. Pekin’s earliest historical records show that Nance and her family were loved and honored by their community.

But prior to 1974, no standard published work on Pekin’s history had ever tried to tell her story – especially the story of the important court case that secured freedom for herself and her children. The Sesquicentennial tells Nance’s story on pages 5-6 and gives a very informative account of the 1838-39 Cromwell v. Bailey and 1841 Bailey v. Cromwell cases.

Unfortunately our knowledge of Nance and her family in the 1970s was incomplete, so the Sesquicentennial’s writer could not provide any information on Nance’s family or Nance’s final years and death in Peoria and burial in Moffatt Cemetery. It was only in 2019 that Nance’s date of death and place of burial were discovered by Debra Clendenen of Pekin and announced for the first time anywhere here at “From the History Room.” Even so, the Sesquicentennial’s account was a big step forward for Pekin’s African-American historiography, and helped give later researchers such as Carl Adams a place from which to start.

Lloyd J. Oliver’s marriage

After the story of Nance Legins-Costley, past Pekin historical works have often retold the story of the marriage of Lloyd J. Oliver of Pekin, an African-American hero of the Spanish-American War. The Sesquicentennial volume also retells this story on pages 154 and 175, though it repeats a mistake regarding Oliver’s Christian name, and the maiden name of his wife Cora, that dates back to Ben C. Allensworth’s 1905 “History of Tazewell County.” Allensworth misread Oliver’s first name as “Howard” instead of “Lloyd,” and misread his wife’s name as Cora “Hoy” instead of “Foy.” Despite that confusion of names, the marriage of Lloyd Oliver and Cora Foy is one of the best remembered events of Pekin’s African-American history, because the organizers of the 1902 Pekin Street Fair chose to honor Lloyd Oliver’s service to his country by making the marriage of this African-American war hero from Pekin a central event of the Street Fair, and thousands of people crowded downtown Pekin to witness the wedding and celebrate their union.

The Ku Klux Klan in Pekin

The 1974 Sesquicentennial does not shy away from a discussion of the darkest and most shameful episode in Pekin’s history, when our city was home to the Ku Klux Klan’s Illinois regional headquarters. On page 83, the Sesquicentennial volume tells of the Klan’s control of the Pekin Daily Times in the early 1920s, reducing the city’s primary newspaper to a mouthpiece of racist, nativist, anti-immigrant, and anti-Catholic bigotry. According to the Sesquicentennial volume, the years when the Pekin Daily Times was owned and operated by three leading Klansmen were also years of careless mismanagement of the newspaper, for although the newspaper had produced bound volumes of its pre-1914 issues, “apparently those volumes disappeared during the Klan years.” As popular as the KKK in Pekin was in certain circles back then, there was also strong opposition and disgust, as indicated by the fact that the Pekin Daily Times then alienated so many of its subscribers that it almost went under.

Another reference to the KKK is found on page 106, in the tragic story of the deadly January 1924 Corn Products explosion. Describing the community’s rescue and relief efforts, the volume says, “Allegedly, the Pekin Ku Klux Klan was also on hand. Thirty-six of its members divided into three shifts to aid in the relief, providing food for the Salvation Army tent; trucks and drivers for transporting both men and materials; and aid to bereaved families in the form of food, fuel, and clothing.”

There was no “allegedly” about it – the Pekin Klan, which had dubbed itself “The All-American Club” – was then an established presence like the men’s clubs and community service groups that were popular at the time, and their members were also affected by the tragedy like everyone else in Pekin. The KKK was also known for ostentatious displays of public charity. The Sesquicentennial on page 109 also mentions that when fire destroyed the Hummer Saddlery on 1 Nov. 1924, the Pekin Klan “offered assistance, including the use of the ‘Klavern’ on First Street (the old Pekin Roller Mills Building).”

The Sesquicentennial on page 172 devotes two rather oddly-worded paragraphs to the subject of the KKK in Pekin, as follows:

“It would be misleading to state that the Ku Klux Klan did not exist in Pekin; in fact, it is fairly certain that Pekin was the headquarters for a Klan — to be precise, organization number 31 of the Realm of the Invisible Empire, whose Grand Titan, in 1924, was recorded as one O. W. Friedrich. Further, the Klan, for a time at least, had their Klavern located at the Old Pekin Roller Mills Plant. The group owned the Pekin Daily Times in the early ‘20’s, and its meetings, policies, and plans were front page news, and its ‘good works’ much praised.

“In all fairness, though, it should be pointed out that the Klan was one of the leading social organizations of the day, and many people belonged in order to participate in the group’s activities, much as one might today belong to some fraternal organization. There seems to have been a distinct inner circle, relatively small in number, and a larger, more social outer circle Much more could be said, but it would serve no real use in this type of publication.”

The choice of words – “It would be misleading,” “In all fairness” – bespeak the writer’s understandable discomfort and abashedness, even shame, regarding this aspect of Pekin’s history. Not only would it be “misleading” to state the KKK wasn’t in Pekin, it would be flat out false. And the apologetic paragraph, “In all fairness . . .,” tends to excuse the KKK’s members for the racism (a word that never appears in the Sesquicentennial) that was so prevalent in America in that era, and that was intrinsic to the Klan’s central aims. This account also must be faulted for failing to acknowledge the Pekin Klan’s hateful intimidation of blacks, Jews, and recently-arrived ethnic families. A more forthright overview of Pekin’s Klan years can be found on pages 21-22 of the late Robert B. Monge’s “WW2 Memories of Love & War: June 1937-June 1946,” which says:

“The decade of the twenties and early thirties brought the KU KLUX KLAN to Pekin. Their ceremonial headquarters were on the second floor of the Pekin Daily Times building located at the southeast corner of Fourth and Elizabeth Streets. The Klan owned and published the paper during 1923, 1924 and 1925, praised its ‘good works’ and gave front page coverage of its meetings, policies and plans.

“For a time it was district headquarters for all the Klan chapters in Illinois. It was a terribly low period for the immigrants who lived here and they were the main target of the KLAN. They were devastated by the Klan’s acts of intimidation. Huge crosses were burned on the land known as Hillcrest Gardens (the present site of Pekin Insurance Company) to intimidate the immigrants. Many of these families huddled in fear in their homes nearby; however, the immigrant men were ready with shotguns just in case they were threatened physically.”

The presence – and absence – of African-Americans in Pekin

Finally, the Sesquicentennial on pages 175-176 devotes eight full paragraphs to Pekin’s African-Americans, and attempts to address the troubling absence of black people from Pekin for most of the 20th century. Much of this account is quite interesting and generally informative, and it covers much of the same ground that this weblog’s 2020 “From the Local History Room” series on Pekin’s African-Americans covered, only in less detail than we have been able to provide here.

The Sesquicentennial account is notably sensitive about Pekin’s reputation and does not acknowledge the role that racist attitudes and the KKK’s presence had, instead blaming the past absence of blacks here on economics and education (which were indeed reasons, albeit certainly not the only reasons). Understandably, the Sesquicentennial volume, written as part of a celebration of Pekin, would not be the appropriate publication to grapple with such issues. Here, then, is the Sesquicentennial’s account, in which he names several individuals and families who have become very well known to me over the past few years):

“But one ethnic element important in earlier generations has slowly become ‘invisible.’ Blacks came to this town by at least 1830 in the person of Nancy, the employee (sic – indentured servant) of the Cromwells discussed in the Overview, and many are mentioned throughout the long period ending after World War I. They had difficulties here, but not the kind of troubles the myth-makers would have us believe.

“The principle problem was the necessity of learning the German language—a barrier to many whites during the same period. Another drawback was the Blacks’ lack of skills, an inevitable problem in an era in which most of them remained uneducated. Nevertheless, they found jobs and homes for their families in the frontier community. According to Bates’ Directory, Nancy apparently lived the remainder of her life in Pekin (a period of about thirty-five [rather, 50] years) after the celebrated Supreme Court appeal argued by A. Lincoln.

“By 1845 the ten-person family of Moses Shipman and the Peter Logan family of four, along with at least six other Blacks, lived in the town. The families of Charles Cramby and John Winslow appear in the records of 1855, as does Benjamin Costly. During the Civil War, no less than ten Blacks from Pekin served in various elements of the Union Army, including Private Thomas Shipman of Company D, 29th United States (Colored) Infantry, who was killed in combat near Hatcher’s Run, Virginia, on March 31, 1865.

“The post-war amendments to the United States Constitution and the new 1870 Constitution of Illinois brought about new openness for the Blacks. Schools and voting were opened to them. The legendary former Sheriff, hero of the Mexican-American War, William A. Tinney (says Chapman in 1879), ‘distinguished himself in his old days by being the first white man in Pekin to lead a Negro to the polls to vote . . .’ Unfortunately, we cannot determine which black resident it was who voted.

“Dozens of others, with both good and poor reputations, lived in Pekin through the years. Anderson Blue, James Lane, and other names appear. ‘James Arnold Washington Lincoln Jackson Gibson’ was the mascot of Company G, 5th Illinois Infantry of the Spanish-American War; and a veteran of that conflict, Howard (sic – Lloyd) Oliver, returned to Pekin in 1902 to marry Miss Cora Hoy (sic – Foy).

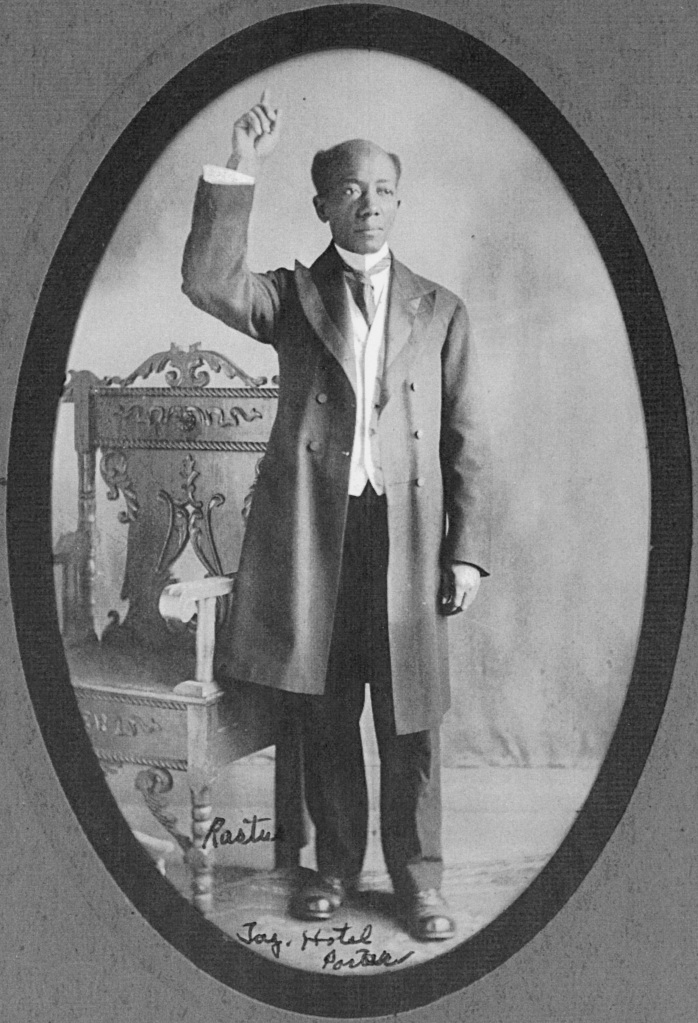

“Then there was ‘Rastus’ Gaines. He is fondly remembered by older citizens as the cheerful, businesslike porter of the old Tazewell Hotel. As the Reverend Erastus Gaines, he made his mark as an evangelist in both Pekin and Peoria. Says one who knew him at the turn of this century, ‘He was uneducated, but within his abilities, he could give a good talk and could get his message across . . . . While we kidded him a lot . . . we liked him a great deal.’“Sam Day, Al Oliver, the families of McElroy, Houston, and Good are names which can yet be recalled by the elder citizens of present-day Pekin. Walter Lee was for many years the masseur at the Pekin Hospital, and for a time had a private practice in the Arcade Building. Many others have come and gone.

“Why is there now this tear in the ethnic fabric of Pekin? Pure economics. When the depression bore down on everyone in the thirties, many persons lost savings, jobs, housing – everything. Black or white, they had to ‘double up’ with friends or relatives to make ends meet. Even though the language barrier no longer exists, and the myth about Pekin’s attitudes have been proven false, Blacks simply have not returned to again add their contribution to the cultural richness of the city which was among the first to recognize them as partners in the progress of an expanding community.”

Any discussion of the African-American experience in Pekin should include not only the stories of Pekin’s black families during the 19th and early 20th centuries, but will have to address Pekin’s reputation as a “Sundown Town,” a community unwelcoming to or hostile to blacks. As we’ve mentioned here before, Pekin’s reputation predates the arrival of the Klan, but the Klan’s strong presence here certainly terrified Pekin’s small population of blacks. U.S. Census statistics show only four blacks in Pekin in 1900 (there were more than that), in 1910 only eight, in 1920 (just before the KKK arrived) a total of 31, in 1930 only one – and in 1940 not a single black person was left in Pekin, something that would not change until the 1990s.

Unlike other Midwestern communities, Pekin never had any city ordinances dictating that blacks had to be out of town by sundown – “unofficial” social pressure and intimidation were certainly present, though. The widespread story of a “sundown” sign on the Pekin bridge remains one of the unresolved mysteries of Pekin’s past, because no direct evidence has ever been produced that Pekin really had such a sign posted on its bridge, the way other “lily-white” Illinois communities posted anti-black signs at their town or city limits. If there ever was such a sign, it was not authorized by Pekin’s city government, and it was probably long gone by the 1960s if not earlier.

The fact that the story has long been so widespread suggests that it is based on truth, and yet the absence of any photographic evidence also suggests that the story could be only a legend. In my own research, the closest I’ve ever come to evidence for the bridge sign is a 14 Oct. 2010 Pekin Daily Times Letter to the Editor written by Randy Hilst, who said he had found the sign (or “a” sign) in an old house in Pekin that had KKK robes and relics. Hilst wrote, “I had the sign verified as to being old by a lady who lived in Peoria, who used to do appraisals at the Illinois Antique Center in Peoria. She said it was the first she had seen but always believed they did exist. We also talked about the possibility that they may have had to be replaced from time to time, so who knows how many were actually made and how many ‘knock-offs’ were made by local racists at the time.”

Until solid documentation is found that might shed light on the old story of the bridge sign, it can only remain a haunting echo of a past that was vastly different from contemporary Pekin’s increasingly racially diverse community.

Next week, “From the History Room” will again feature an article in keeping with Black History Month, telling the story of the three Pekin-area ministers who joined the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to march for African-American civil rights in Alabama in 1965.