By Jared L. Olar

Local History Program Coordinator

For this third in our series of Pekin Bicentennial Black History Month articles, we’ll highlight a selection of just a few of the many stories of Abraham Lincoln and his ties to Pekin. These stories span Lincoln’s life and career as a prairie lawyer and politician.

Lincoln’s broken oar (1832):

The first time Abraham Lincoln ever came to Tazewell County was in 1832. After the Black Hawk War during which Lincoln served in the Illinois Militia, Lincoln took a canoe down the Illinois River on his way back home to New Salem. As he neared Pekin, Lincoln’s oar broke, so he stopped his canoe on the riverbank at Pekin, carved himself a new oar, and then shared a hot meal with some of Pekin’s pioneer residents before resuming his trip down the river.

Bailey v. Cromwell (1841):

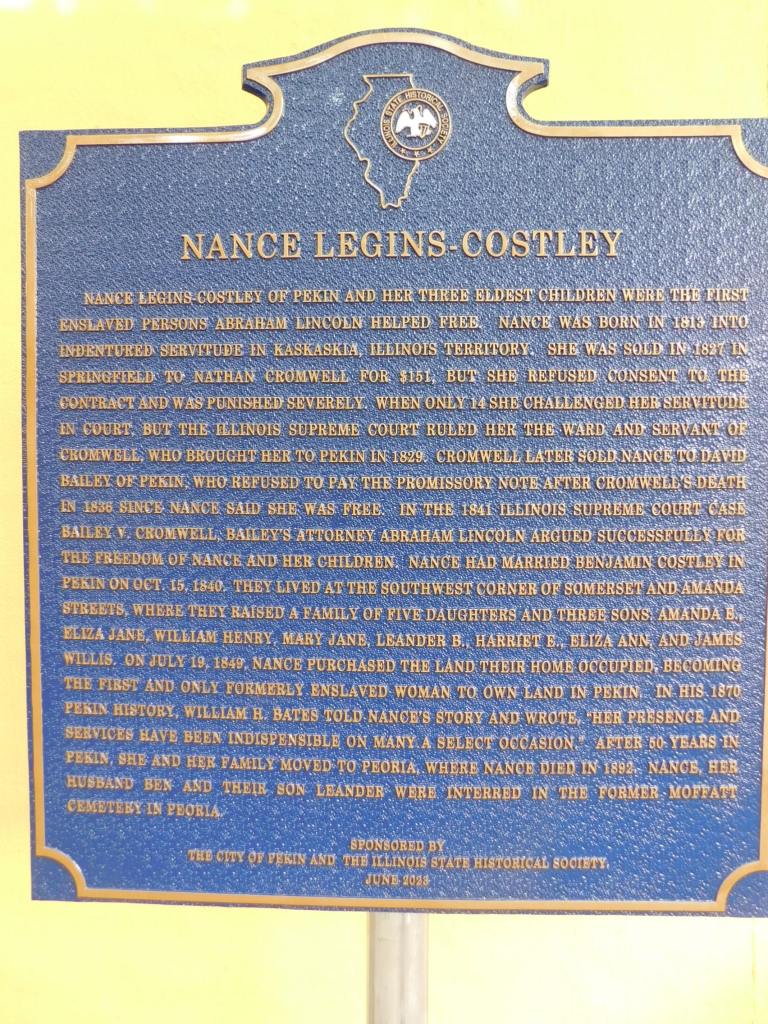

Pekin co-founder Nathan Cromwell was a land speculator who owned many lots in early Pekin. He died in St. Louis, Missouri, while on his way to Texas to start another land speculation scheme there. Cromwell is also known to history as the (purported) owner of an African-American indentured servant named Nance Legins-Costley (1813-1892). Cromwell purchased Nance in Springfield and brought her to Pekin in 1829. Nance, however, insisted that she was free because she had never given her consent to become an indentured servant as Illinois law required of all contracts of indentured servitude.

Before leaving for St. Louis, Cromwell sold Nance to another early Pekin settler named David Bailey, who promised to pay Cromwell $376.48 for Nance. However, when he learned Nance insisted she was free, Bailey (of an abolitionist family), let Nance live as a free woman and declined to pay off the promissory note to the Cromwell Estate. The Cromwell Estate then sued Bailey in Tazewell County Circuit Court in the 1838-9 case of Cromwell & McNaghton v. Bailey. The firm of Stuart & Lincoln represented Bailey, and Lincoln presented clear evidence that there was no proof Nance was ever Cromwell’s indentured servant, but nevertheless the court ruled in favor of the Cromwell Estate and ordered Bailey to pay $431.97.

Bailey then appealed to the Illinois Supreme Court in the 1841 case of Bailey v. Cromwell & McNaghton. During arguments on 23 July 1841, Lincoln pointed out that the Chief Justice had no papers saying he was an indentured servant and therefore he was considered a free man; that several lawyers in the court had no indentured servitude papers and they were free men; and Nance had no such papers either, so the Court must rule that she is a free woman. Justice Sidney Breese therefore ruled that Nance and her three children Amanda, Eliza Jane, and William Henry were free. Thus, Nance and her children were the first African-American slaves to be freed through the direct help of Abraham Lincoln. (Her son William Henry Costley later served in the 29th U.S. Colored Troops in the Civil War, and was present in Galveston, Texas, at the first Juneteenth.)

The Pekin Agreement (1843):

Lincoln’s first political campaign was 28 years before he became president. In 1832, he was one of 13 men seeking a Sangamon County seat in the Illinois House of Representatives. Lincoln only garnered 657 votes, however, for his service in the Black Hawk War had limited his ability to campaign.

Two years later, Lincoln again sought the same seat in the Illinois House, coming in second and losing by only 14 votes. In that election, Lincoln ran as a member of the Whigs, a conservative party that was one of the predecessors of the Republican Party. Trying a third time for the same seat in 1836, Lincoln was victorious, defeating 16 other candidates (including four of his fellow Whigs). Lincoln was reelected to the Illinois House in 1838, but came in fifth in a very crowded field in 1840, losing to another member of the Whig Party.

Three years after that, Lincoln first began to set his sights on a national office, hoping to win his party’s nomination for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives for the 7th Congressional District of Illinois (which then encompassed the counties of Sangamon, Morgan, Scott, Cass, Menard, Tazewell, Logan, Putnam, Woodford, Marshall, and Mason).

It was Lincoln’s political ambitions in 1843, and those of two other prominent Illinois Whigs, that led to “the Pekin Agreement.” This was a pact arranged at the convention of the Illinois Whig Party, which was held in Pekin on 1 May 1843. At the Pekin convention, the Illinois Whigs were divided among the supporters of Lincoln, Gen. John J. Hardin, and Edward Dickinson “E. D.” Baker, each of whom hoped to be the candidate for the 7th Congressional District seat. For the sake of party unity, it was apparently agreed that the three men would serve only one two-year term in Congress. Hardin got their party’s nomination coming out of this convention, while Lincoln’s resolution was approved that Baker should be the party’s nominee in the 1844 Congressional election.

After Baker’s term, however, the Pekin Agreement collapsed. This is how the “Papers of Abraham Lincoln” database describes the agreement, how it fell apart, and the effect it had on Lincoln’s career in politics:

“At a Whig convention in Pekin in May 1843, an agreement was made between Lincoln, Edward D. Baker, and John J. Hardin that seemed to establish a one-term limit on the prospective Whig congressmen. Hardin and Baker having each served one term, Lincoln believed that the 1846 nomination should have been his. While Lincoln set out to solidify his support in the district, Hardin proposed that the convention system for the nomination be thrown out in favor of a primary election. Lincoln rejected Hardin’s proposal on January 19, 1846, and Hardin subsequently declined the nomination entirely.”

That paved the way for Lincoln’s election to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1846. He served a single term in Congress, from 1847 to 1849. Five years later, Lincoln was elected to the Illinois House in 1854, but chose not to take his seat because by then he had his eyes on a seat in the U.S. Senate. But neither in 1854 nor in 1858 (the year of the famed Lincoln-Douglas debates) was Lincoln able to win a Senatorial seat.

Donor to First Baptist Church (1850):

Rev. Gilbert S. Bailey, a friend of Lincoln, organized First Baptist Church of Pekin in 1850 and initiated a building fund campaign. Bailey wrote to Lincoln asking if he would become a subscriber to the building fund. Lincoln’s religious views are hard to pin down (other than being generally Protestant Christian), but in any case Lincoln responded favorably to Bailey’s request, donating what was then a liberal sum of $10 toward the construction of the original First Baptist Church of Pekin, which was built at the southwest corner of Elizabeth and Fifth streets. The original church measured 32 ft. by 44 feet. That site is now the parking lot of the Pekin Township offices, and First Baptist Church is now located at 700 S. Capitol St. The church still has the original subscribers list, including Lincoln’s name, in its records.

Tazewell County Courthouse stories (1850s):

On a few occasions, Lincoln was called upon to serve temporarily as Acting State’s Attorney of Tazewell County, working as the county’s prosecutor instead of as a defense attorney. One such case was in 1853, when Thomas Delny raped a 7-year-old girl named Jane Ann Rupert, pointing a gun at her head to force her to comply. Just before this case was tried, the State’s Attorney had left on a vacation, so the presiding judge appointed Lincoln as Acting State’s Attorney. The jury found Delny guilty, and the judge sentenced him to 18 years in prison. However, after serving only six years of his sentence, Illinois Gov. William Henry Bissell pardoned Delny and set him free.

A humorous episode involving Lincoln occurred during the early days of the 1850 courthouse in Pekin: one day when court was in session, a bat got into the court room and disrupted court proceedings. First the witness testifying on the stand began watching the bat fly back and forth. Then the judge’s attention was diverted to the bat. Then everyone in the courthouse began watching the bat, and a lawyer even jumped up and, taking a bullwhip from his saddlebag, he began snapping his whip at the bat. Finally the judge asked the tall and lanky Lincoln to try to get the bat out of the courtroom. As the judge tried to resume court proceedings and laughter filled the courtroom, Lincoln first tried chasing the bat as he twirled his coat, using it like a net, but when that didn’t work, he grabbed a broomstick and flailed it about, chasing the bat around the courtroom until he finally managed to drive the bat out the window.

Another colorful tale from one of Lincoln’s visits to Pekin is recorded by Eugenia Jones-Hunt (1846-1947) in her book, “My Personal Recollections of Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln.” Jones-Hunt includes a story from a man named Seth Thandler, who attended a Republican Party picnic on the Tazewell County Courthouse lawn around 1855. According to Thandler, Lincoln was there, along with Judge Lyman Trumbull (who later co-authored the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery in the U.S.) as well as abolitionist political leaders Isaac Newton Arnold and Rev. Owen Lovejoy. Thandler says that during the picnic, somehow his hat was placed in the coffee boiler — but everyone at the picnic seemed to enjoy the unusual “hat” flavored blend of coffee, for they all said the coffee that day was delicious.

Lincoln’s speech in Pekin (1858):

Joshua Wagenseller, a prominent Pekin merchant, was a leading member of the local Whig Party (later a Republican) and a good friend of Abraham Lincoln, who several times visited or stayed at the grand and beautiful Wagenseller house during his visits to Pekin. Lincoln is reported to have given at least one speech from the front porch of the Wagenseller house, which was located at a spot that is now the southwest intersection of Second Street and Broadway. Lincoln and William Kellogg, then a U.S. Congressman, visited Joshua Wagenseller’s home on 5 Oct. 1858 during the period of the Lincoln-Douglas debates. Lincoln and Kellogg then gave speeches at the courthouse square — Lincoln in the afternoon (introduced by Judge Bush), Kellogg in the evening.

Here is the account of the “Lincoln Rally” from The Tazewell Register, Thursday, Oct. 7, 1858:

Mr. Lincoln met with a very cordial reception from his friends on Tuesday [Oct. 5], and if they are satisfied with the demonstration, we see no reason why democrats should not be. The procession, numbering about one hundred teams, averaging six persons to a team — one third of whom however, were not voters — passed through the streets several times, and finally brought up at the court-house square, where Mr. Lincoln, accompanied by his abolition friend Webb and others, mounted the stand. T. J. Pickett gave the cue for “three cheers;” after which Judge Bush delivered an address of welcome suitable to the occasion. Mr. Lincoln spoke for about two hours, and then left for Peoria on his way to Galesburg, where he has a discussion today with Judge Douglas.

The crowd in town was easily estimated, and we think we are liberal enough allowing three thousand, including men, women, and children. Of course, besides the democrats, there was a large number of old line whigs present who have no idea of amalgamating with abolitionists, even to oblige Mr. Lincoln.

Trumbull was not here to take the place assigned in the bills, but Judge Kellogg was on hand, and spoke in the courthouse at night. We were not present, but understand he appeared as the peculiar advocate and representative of Lyman Trumbull, and repeated the charges for which Judge Douglas had branded Trumbull as “an infamous falsifier.”

We have conversed with a number of democrats who were in town on Tuesday and Saturday, and they assure us that the two meetings demonstrate beyond a doubt that the county is sure to go for Douglas.

And here is the account of Lincoln’s speech from the Peoria Transcript, Tuesday, 5 Oct. 1858:

Mr. Lincoln was welcomed to Tazewell county and introduced to the audience by Judge Bush [John M. Bush, probate judge in Pekin] in a short and eloquently delivered speech, and when he came forward, was greeted with hearty applause. He commenced by alluding to the many years in which he had been intimately acquainted with most of the citizens of old Tazewell county, and expressed the pleasure which it gave him to see so many of them present. He then alluded to the fact that Judge Douglas, in a speech to them on Saturday, had, as he was credibly informed, made a variety of extraordinary statements concerning him. He had known Judge Douglas for twenty-five years, and was not now to be astonished by any statement which he might make, no matter what it might be. He was surprised, however, that his old political enemy but personal friend, Mr. John Haynes [sic – James Haines] — a gentleman whom he had always respected as a person of honor and veracity—should have made such statements about him as he was said to have made in a speech introducing Mr. Douglas to a Tazewell audience only three days before. He then rehearsed those statements, the substance of which was that Mr. Lincoln, while a member of Congress, helped starve his brothers and friends in the Mexican war by voting against the bills appropriating to them money, provisions and medical attendance. He was grieved and astonished that a man whom he had heretofore respected so highly, should have been guilty of such false statements, and he hoped Mr. Haynes was present that he might hear his denial of them. He was not a member of Congress he said, until after the return of Mr. Haynes’ brothers and friends from the Mexican war to their Tazewell county homes—was not a member of Congress until after the war had practically closed. He then went into a detailed statement of his election to Congress, and of the votes he gave, while a member of that body, having any connection with the Mexican war. He showed that upon all occasions he voted for the supply bills for the army, and appealed to the official record for a confirmation of his statement.

Mr. Lincoln then proceeded to notice, successively, the charges made against him by Douglas in relation to the Illinois Central Railroad, in relation to an attempt to Abolitionize the Whig party and in relation to negro equality.

After finishing his allusions to the special charges brought against him by his antagonist, Mr. Lincoln branched out into one of the most powerful and telling speeches he has made during the campaign. It was the most forcible argument against Mr. Douglas’ Democracy, and the best vindication of and eloquent plea for Republicanism, that we ever listened to from any man.

Seth Kinman and his chairs (1865):

One of Pekin’s early hotels was the Eagle Hotel, located on the south side of Court Street at the intersection of Front Street (now within Pekin Riverfront Park). Pekin’s pioneer historian William H. Bates confusingly claimed Tazewell House/Bemis House was later located on the same site, but Tazewell House was on the north side of Court Street, across the street from where the Eagle had previously been. The Eagle Hotel first opened its doors in 1848, and it was owned and operated by a Tazewell County pioneer named Seth Kinman (1815-1888), who later headed out West and became a renowned mountain man and hunter in California.

Abraham Lincoln is not known to have stayed at the Eagle during his visits to Pekin, but more usually stayed at Tazewell House across the street. Nevertheless, Seth Kinman was a friend and great admirer of Lincoln. On 26 Nov. 1864 during a visit to the White House, Kinman presented the president with a unique chair that he had made out of elk horn and bear claws. He later gave a similar chair to President Andrew Johnson. As sharp as the antlers and claws were, Lincoln and Johnson probably would have had to take special care if they’d ever tried to sit in them. Presumably these unusual gifts were meant to be decorative only.

The year after presenting the chair to Lincoln, Kinman returned to Washington, D.C. Kinman claimed to have been a witness to Lincoln’s assassination at The Ford Theatre, and newspaper reports on Lincoln’s funeral mention that Kinman walked in Lincoln’s funeral procession.